For current info please visit detroitmi.gov

Midwest-Tireman History

Midwest-Tireman: A Snapshot of History

The framework area, the Midwest-Tireman neighborhood, has a rich history in the City of Detroit. It was a thriving neighborhood whose prosperity was tied to the African American middle class and blue color working-class experience. This neighborhood has gone through various name iterations. Some names used for the community include “The Westside,” “The Old Westside,”1 and “The North of Warren Community.” The neighborhood initially consisted of people from European countries, such as Germany and Poland, and the population was primarily Jewish.2 1920 saw the influx of African Americans into the neighborhood.3

While contemporary scholars have not come to a shared conclusion as to why African Americans moved to the West Side,4 the memoir published by the West Side residents in 1997 mentions “a quest for better housing” as a cause for the migration.5

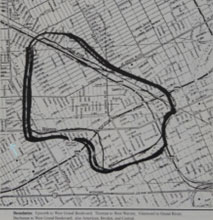

Neighborhood Bounding Area

The Old West Side consisted of several neighborhoods. The boundaries were Grand river on the east, Buchanan on the south, Tireman on the North, and Epworth on the West.6 From the 1920s to the 1950s, the area became desirable for middle-income and blue color jobs African Americans to call home. The neighborhood was a mix of well-maintained single and multifamily houses with thriving commercial district corridors along Tireman and Grand River Avenues.7 Historically, the area, south of Tireman Avenue and Grand River Avenue, is known for being the first Black enclave established outside the traditional Black Bottom and Paradise Valley.8

The current neighborhood framework study area is bounded by Oakman, Clover Lawn, and Roselawn on the western edge. On the South is Warren. On the Southeast and Northeast boundaries, there are the I-94 and I-96. Tireman and Livernois intersect the neighborhood horizontally and vertically, respectively

Migration From The South To The West Side

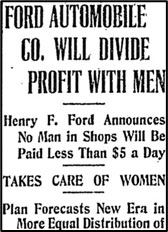

1920 saw the influx of African American population. It began in 1914 when Ford Motor Company announced they would pay unskilled laborers $5 per day to work in their factory. The news reached the deep South, and the US saw one of the largest population migrations in its history. 16,000 African Americans were leaving the South per month from 1916 to the 1920s. By 1930, the number of African Americans living in Detroit was over 120,000. Most of the new population settled in the Black Bottom area, near the east side between Woodward and Chene.10

However, due to limited job opportunities and inadequate housing options, there was another migration by 1920. In their quest for better housing for their families this time, Detroiters moved to areas West of Woodward Avenue11 and other areas of the city, such as Tireman Avenue.12

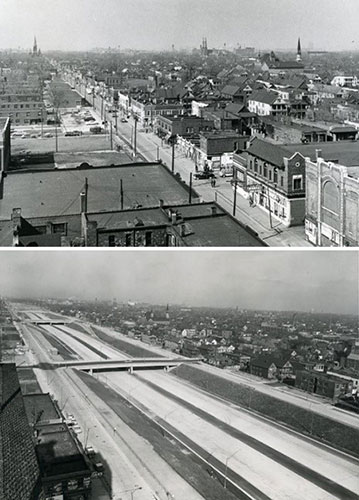

Urban Renewal and the National Interstate and Defense Highway Act

Source: Detroit Historical Society

It is also posited that the redevelopment of the neighborhoods Black Bottom and Paradise Valley as part of the ‘urban renewal’ initiative caused African Americans to relocate to neighborhoods throughout the city, including the West Side. Black bottom and Paradise Valley were vibrant communities composed of a heterogeneous population from various backgrounds and social classes. However, it also had a considerable amount of poverty, which included poor housing conditions and sanitary conditions.13

To address these conditions, the 1949 National Housing Act and 1956 National Highway Act were enacted that gave the City of Detroit funds to begin urban renewal projects, replacing the vibrant Black Bottom and Paradise Valley with the construction of Chrysler Freeway (which includes I-375) and Lafayette Park, a mixed-income development designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.14

Source: Arch Daily- Photograph by Jamie Schafer

Many residents relocated to large public housing projects such as the Brewster-Douglass Housing Projects Homes and Jeffries Homes. Former Black Bottom residents also moved to neighboring communities east and west of the City, where the African-American middle class had lived since the 1920s.15 As a result, the West Side grew rapidly and, by 1940, contained about a third of the city’s African American population. It was the largest Black neighborhood outside of Black Bottom.16

Homeownership

Compared to the Black Bottom, the West Side was doing better socio-economically. The Black Bottom had a ten percent homeownership at the beginning of World War II, with sixty percent of its dwellings considered substandard.

On the other hand, homeownership rates in West Side were between forty and forty-nine percent, much higher than for White residents citywide. Most houses were newly constructed, with only seventeen percent of substandard quality.17

Employment and Local Businesses

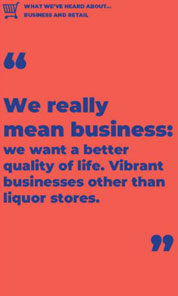

As previously mentioned, the automobile industry was a key factor contributing to the influx of African Americans in the “Old Westside.” The largest employer of African American workers was the Ford Motor Company and Kelsey Hayes Wheel Company.18 Other major employers were the Lincoln Livernois Plant, the Michigan Central Railroad, and the United States Post Office.19,20 By 1950, due to the influx of African Americans, the neighborhood saw the establishment of black-owned businesses. These were over 300 hundred mostly family-owned establishments on Tireman Avenue that provided services catered to the community’s needs, such as restaurants, beauty and barber shops, dry cleaners, gas stations, appliance stores, drug stores, and several distributing companies.21

Growth of Churches

The population demographic change caused the establishment of black churches in the neighborhood. These religious establishments include the Harford Memorial Baptist church, St. Stephan African Methodist Episcopal Church, St. Cyprian’s Episcopal Church, and Tabernacle Missionary Baptist church.

These churches were established from a period of 1917 to 1926.22,23,24,25 Some of these churches have since relocated outside the neighborhood boundary.26

Arts and Recreation

Source: City of Detroit Planning and Development Department

The influx also had a ripple effect on the growth of music and entertainment in the area that catered to the needs of a burgeoning Black audience. Establishments such as the ‘Blue Bird Inn’ located at 5021 Tireman Ave played a significant role in the music landscape in Detroit.27 They created a space for modern jazz, R&B, soul music, early rock and roll, and Motown to flourish. Also, organizations such as the Nacirema Club served as a place for young middle-class African American gentlemen to congregate and socialize.28

Restrictive Covenant and Limited Housing Opportunities

The migration of African Americans into Old Westside resulted in racial tension, especially due to the enforcement of racially restrictive covenants or “racial covenants” and the limitations they imposed on housing availability in the area. Racial covenants are agreements, usually in the form of deeds between buyers and sellers of property, that limit the seller’s property rights. Specifically, racial covenants state that the seller will not sell, rent, or lease property to minority groups.29 Some covenants generally barred “non-Caucasian” groups, while others would list specific races, nationalities, and even individuals with disabilities.30 Therefore, racially restrictive covenants were widespread tools of discrimination during the first half of the 20th century.31

Historians claim that incorporating racial covenants into deeds became popular due to the Supreme Court’s 1917 decision that municipally mandated racial zoning was unconstitutional.32 In Buchanan v. Warley, the Court overturned Louisville, Kentucky’s racial zoning ordinance, which forbade people of color to occupy houses in blocks where white persons occupy the majority of the houses.33 This practice interfered with the right to sell or otherwise transfer one’s property and violated the Fourteenth Amendment, specifically its protections for freedom of contract.34

Racially restrictive covenants gained further traction in 1926 after the Corrigan v. Buckley case. In 1926, James J. Buckley sued his neighbor Irene Hand Corrigan for selling her property to two African Americans, Dr. Arthur Curtis and Helen Curtis. He claimed that she violated the restrictive covenant signed by Mr. Buckley and most of the white residents of his block, including Ms. Corrigan. The covenant prevented present and future owners from selling or renting their properties to “persons of the negro race or blood.” The Supreme court ruled in favor of Mr. Buckley. The Court saw the covenants as a form of private contract and, therefore, constitutional.35 They defined racially restrictive covenants as a private action exempt from the approval of the State, and developers and white homeowners were free to construct racially exclusive communities through legal agreements.36 They also dismissed any follow-up appeals by Ms. Corrigan and her representatives from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).37

Key Cases That Delegitimized Restrictive Covenants

The landmark case that delegitimized racial covenants was Shelly vs. Kraemer, where the Court revisited and overturned Corrigan v. Buckley and held that judicial enforcement of racially restrictive covenants constituted discriminatory governmental action and is in violation of the Constitution.38 In the City of Detroit and especially the study area, two cases that weakened the efficacy of racial covenants were the trial of Dr. Ossian Sweet and McGhee v. Sipes. The McGhee case is also significant for its connection to the Shelley v. Kraemer case, which was argued by the NAACP’s lawyer Thurgood Marshall and decided in 1948.39 This case marked the ‘legal’ end to the enforcement of racially restrictive covenants in housing.40

The Trial of Ossian Sweet

In 1921 prominent black medical doctor Ossian Sweet a 26-year-old graduate from Harvard University medical school decided to settle in Detroit. He bought the house at 2905 Garland on the east side of Detroit. This was an area of mostly white foreign-born factory workers. Dr. Sweet intended to raise his little girl in good surroundings. However, after purchasing the house, He received death threat letters saying he would be killed if he tried to move into his house.

On September 8, 1925, Dr. Sweet, his wife Gladys Sweet, and nine gun-carrying associates moved into the house under police escort, the next night, a large crowd began pelting the house with rocks and bottles. As the crowd rushed the house, gunshots were fired from the second-story windows, killing one man in the mob and seriously wounding another.41

Dr. Ossian Sweet and his family were arrested and charged with the murder. There were two prolonged and exhaustive trials. The first trial was on November 1925.42 The NAACP selected Clarence Darrow, a renowned criminal lawyer, to defend the Sweets, and the first trial resulted in a deadlocked jury, as they could not come to a verdict. The defendants were retaken to court. This time, Clarence Darrow argued that if the roles were reversed and a white man had shot and killed a black man while protecting their homes against a mob of black people, it would have been applauded. The jury finally ruled that the defendants had acted in self-defense. 43 The presiding Judge, Frank Murphy instructed the jury that “a man’s house is his castle” and that Dr. Sweet had the right to defend it if he had good reason to fear for the lives of his family or their property. He noted these rights applied to both black and white people.44 This case was a milestone for the rights of black people to own property and defend it.

Source: Detroit Public Library - Digital Collections

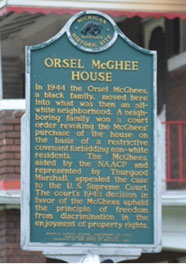

Mr. Orson McGee worked at the National Bank of Detroit before becoming a custodian at the Detroit Free Press. He eventually became superintendent of the maintenance crew and worked there until his retirement in 1963.45 His father was White, and his mother was Black.46 Therefore he was born a light-skinned African American and often passed as White.47 His wife, Minnie McGhee (nee Leatherman Simms), was dark-skinned. She was an elementary school teacher in Elberton, Northern Georgia48 before she moved to Detroit in 1938 and worked as a postal clerk. She met Mr. McGhee soon after, and they married on November 26, 1938. 49

The McGhee family purchased the house at 4626 Seebaldt Street on November 30, 1944, and moved in on December 22. The house was situated in the White part of the neighborhood. It was owned by a White man named Walter Joachim, who was willing to quickly sell it to a Black family because he was eager to move his family to California.50 Since Mr. McGhee often passed as White and got along well with his White coworkers, he believed that any initial opposition to their move would soon dissipate.51

However, on January 7, 1945, a group of neighbors confronted the McGhees.52 Ten members of the Northwest Civic Association, the local neighborhood association, came to the house and spoke with the McGhees. This group included Benjamin Sipes, who lived next door at 4634 Seebaldt Street with his wife, Anna. They informed Mr. McGhee with a letter stating that the property was restricted to people of the “Caucasian race” and that since the McGhees were “Negroes” they had to vacate. If they did not, the association would take them to court.53

On January 30, 1945, Mr. Sipes filed a bill of complaint with the Wayne County Circuit Court.54 The restriction violation mentioned above was the basis for Benjamin Sipes and the Northwest Civic Association’s suit against the McGhees. The case, Sipes v. McGhee, was brought before the Wayne County Circuit Court on May 28 and 29, 1945.55 Willis M. Graves and Francis M. Dent, from the NAACP’s Detroit chapter, initially took the McGhees case.56 However, they eventually stepped down and allowed Thurgood Marshall, who had more experience in front of the United States Supreme Court, to lead the case. Collectively, they argued that restrictions on the right to use and occupy real estate as a residence went against the Fourteenth Amendment (and the Civil Rights Act of 1866): since no state can deny civil rights due to race, color, religion, or national origin. Therefore, judicial enforcement of a racially restrictive covenant was a denial of the civil rights of the McGhees. 57

On May 3, 1948, the United States Supreme Court decreed that racially restrictive covenants were seen as private actions and therefore were not banned themselves. However, their enforcement by states (e.g., forcing African Americans out of their homes by court order) violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. These covenants now had no legal force backing them.58

It is important to note that the practice of writing racially restrictive covenants into deeds was not illegal until 1968. The Federal Fair Housing Act made it unlawful to refuse to sell, rent to, or negotiate with any person because of that person’s inclusion in a protected class.59

Therefore, it can be surmised that the impacts of milestone cases like McGhee v. Sipes, Shelly v. Kreamer, the trial of Ossian Sweet, and the Federal Fair Housing Act allowed African Americans to have more legal access to housing options in Detroit and the Midwest-Tireman Framework study area.

Population and Socio-economic Decline of the Midwest

Source: City of Detroit Planning and Development Department

Unfortunately, 1950 saw a significant decline in Detroit’s population and infrastructure resources. This decline is mostly attributed to the automobile industry moving outside the city limits into the suburbs and shifting production overseas. At the same time, many autoworkers were leaving the city to live in the suburbs, further weakening the city’s tax base.60 From 1930 to 2021, Detroit’s population dropped by 50% from 1,568,662 to 659,751. The Midwest-Tireman neighborhood was not exempt from this mass exodus. In fact, within the same time span, its population declined from 59,081 to 10,741, almost 82%.61 It began with the White population moving out, followed by the African American middle class relocating to other parts of the city. 62 Even the lower economic class began moving to the outskirts of the neighborhood, at the Northwest of the framework area at 12th Street, Dexter Ave, Linwood neighborhood.63 Due to depopulation and the corresponding lack of resources, the neighborhood once known for its thriving Black business, churches, and live music is now known as the ‘forgotten neighborhood.’

Recapture the Past

Fortunately, since 1993 structures such as the St. Cyprian’s Episcopal Church, Nacirema Club, and Blue Bird Inn have been designated historically significant buildings. The Orsel McGhee house has been added in the National Register of Historic Places.64 Even more encouraging is the active involvement of local organizations in rehabilitating historic structures. For example, the Detroit Sound Conservatory (DSC) has secured $40,000 to replace the roof and secure the structure for the Blu Bird Inn.65 The DSC has launched a crowdfunding campaign to raise $30,000 to bring the project into the next phase. A grant from the National Trust for Historic Preservation will match the funds.66 They also raised nearly $300,000 in capital funds with grants from The Kresge Foundation, Detroit Regional Chamber, and The National Trust for Historic Preservation African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund.67 The Blue Bird Inn can once again be a neighborhood hearth for the community in the form of a music venue, gathering space, and cultural education center.68 Also, the St. Cyprian Church has recently been purchased by Class Act Detroit, and there are plans for the church to become a Cultural Health Center.

The infrastructure for a healthy and thriving neighborhood is there, and although structures exist, there still needs to be the capacity to reuse or restore them. Therefore, while it may not be possible to recapture the past, it is possible to begin to chart a course for a new future.